Table of Contents

- 1 What is kidney cancer?

- 2 What is the function of the kidneys?

- 3 Symptoms of kidney cancer

- 4 Diagnosis of kidney cancer

- 5 Treatment of kidney cancer

- 6 Treatment of localised kidney cancer

- 7 Treatment of locally-advanced kidney cancer

- 8 Treatment of metastatic kidney cancer

- 9 General information about kidney cancer

- 10 In need of support?

What is kidney cancer?

Kidney cancer is a malignant cell growth (a tumour) in the kidneys. Its medical name is renal cell carcinoma. However, in about 15% of cases, a kidney tumour may be benign (non-cancerous).

Kidney cancer is a general term. There are many variations of tumours in the kidney and stages of the disease. Your treatment and experience depend on the specific characteristics of the tumour and the expertise of your medical team.

Kidney cancer represents around 3% of all cancer diagnoses worldwide. In the last twenty years, the number of cases of kidney cancer worldwide has increased slightly, but the survival rate has also gone up in most of regions. Because of the more frequent use and improvements in ultrasound and CT imaging technology, more kidney cancers are now diagnosed at an earlier stage.

Men are more likely to be diagnosed with kidney cancer than women. Most people are diagnosed between the ages of 60 and 70.

Certain lifestyle factors can increase the risk of kidney cancer, including smoking, being overweight, high blood pressure, and metabolic syndrome. The best way to lower your risk is to quit smoking, maintain a healthy weight, and stay active.

Screening everyone for kidney cancer isn’t practical because the disease isn’t very common, and there aren’t any reliable tests yet for finding it in urine or blood. Using a CT scan for screening isn’t recommended because it’s expensive and involves radiation exposure.

The chapters in this series provide general information about kidney cancer, diagnosis, and treatment options. Discuss your individual situation with your doctor.

Symptoms of kidney cancer

In most cases kidney cancer is asymptomatic, which means that there are no clear symptoms to indicate it. Most kidney tumours are found during a routine ultrasound or a similar imaging procedure for other conditions such as back pain.

About 1 in 10 people do experience symptoms like pain in the side of the body, abdominal mass or blood in the urine. This could be a sign that the disease has advanced. Some people can also experience so-called paraneoplastic syndromes. These are reactions the body can have to any type of cancer and may include high blood pressure, weight loss, fever, anaemia, muscle mass loss, and loss of appetite. Syndromes more commonly associated with kidney cancer include changes in liver enzymes and blood platelets. These changes are usually discovered during tests and normally do not cause any symptoms.

Bone pain or a persistent cough could be signs that the cancer has spread through the body. This is known as metastatic disease.

Diagnosis of kidney cancer

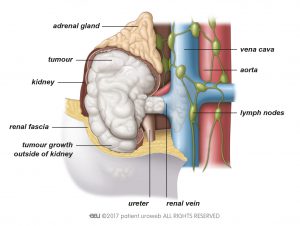

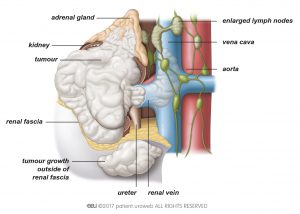

Because there are several types of kidney tumours, the doctor does a series of tests to better understand your specific situation. These tests include a medical history, laboratory tests and scans. Sometimes a family history is also taken. A CT scan or MRI scan will reveal the size of the tumour and if it has invaded local veins, lymph nodes, or surrounding organs. This is important to determine further treatment. The doctor may also perform a physical examination and take blood and urine for testing.

With the results of your scan, the urologist can define the stage of the disease. By analysing tumour tissue, received either during surgery or biopsy, the pathologist determines the subtype of the tumour and whether or not it is an aggressive form. Together, the stage, subtype, and aggressiveness of the tumour form the classification.

Classification of the kidney tumour is used to estimate your individual prognosis. Based on this individual prognosis your doctor will discuss the best treatment pathway for you.

There are three main types of kidney cancer that doctors see most often: clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC), papillary RCC, and chromophobe RCC. Of these, papillary RCC and chromophobe RCC usually have better outcomes than clear-cell RCC. In addition to cancerous tumours, there are also non-cancerous (benign) tumours that can develop in the kidneys. The two most common ones are angiomyolipoma (AML) and oncocytoma. These benign tumours don’t usually spread like cancer, and they generally have a better outcome.

In some cases you may need additional tests to check your kidney function. This is important if you only have one kidney or if you are at risk of kidney failure because you have diabetes, high blood pressure, chronic infections, or a kidney disease.

Imaging is important for the diagnosis and classification of kidney tumours. Most common imaging techniques are ultrasound, CT scans, and MRI. In some cases a biopsy is done to get more insight into the specific characteristics of the tumour.

If you have a cystic tumour in your kidney, your doctor might use a system called the Bosniak classification. This system helps predict whether a kidney cyst is cancerous by placing it into one of five categories based on what it looks like on a CT or MRI scan.

If your cyst is classified as category 1 or 2, it usually means it is likely benign (non-cancerous). However, if your cyst is classified as category 2F, 3, or 4, it’s important to discuss it with your doctor, as these categories may have a higher risk of being cancerous.

Contrast-enhanced scan

After a tumour is detected, the doctor first needs to know whether it is malignant. A contrast-enhanced ultrasound, CT, or MRI scan of the abdomen provides information about this. CT and MRI scans also show:

- The location and size of the tumour.

- Whether or not you have enlarged lymph nodes.

- Whether or not the tumour has spread into the veins within the kidney (called renal veins) or even further into the large vein that carries blood to the heart (called the vena cava).

- Whether or not the tumour has spread to neighbouring organs, such as the adrenal gland, liver, spleen or pancreas.

- Whether the urinary tract is affected by the tumour.

For a contrast-enhanced scan, a contrast medium is administered through an IV, usually in your arm. The contrast medium highlights your veins and arteries by giving them a different colour in the pictures taken during the scan. This type of scan allows the radiologist to analyse the tumour. The results will guide the treatment you receive.

If you are allergic to contrast medium, you will receive an MRI or CT scan without contrast-enhancement.

If you have a small or unclear mass or tumour in your kidney that was found on a CT scan, your doctor might recommend an MRI to get more detailed information. This can help better understand the type of tumour and determine whether it is likely cancerous or not.

If your doctor thinks the cancer may have spread to the lungs, you will get further tests, like a CT scan. You may need a bone or brain scan if you have symptoms such as bone pain or epileptic seizures. These scans are done to see whether the cancer has spread to bones or the brain.

Renal tumour biopsy

During a renal tumour biopsy, one or more samples of tumour tissue are taken. First, you receive local anaesthesia. Then the doctor inserts a needle through your skin and uses ultrasound or CT imaging to locate the tumour. The tissue samples are analysed by the pathologist in order to help determine future treatment.

Renal biopsy is not standard procedure in the diagnosis of kidney cancer. You may need a biopsy in case:

- The results of your scan are not clear enough.

- You have a small tumour which could be treated with active surveillance.

- You have a small tumour which could be treated with radiofrequency ablation or cryotherapy.

- You have an advanced kidney tumour that has spread to other parts of your body, and your doctor is planning treatment that targets the whole body, called systemic treatment.

Biopsies may cause blood in the urine. In rare cases, they can cause more severe bleeding. A renal tumour biopsy is generally a harmless procedure.

Prognosis

The outlook (prognosis) for kidney cancer depends on several factors, including the stage of the tumour, its size, the grading system used (WHO/ISUP), the type of kidney cancer, and your overall health. There are also different tools, like the Leibovich and VENUSS score, that doctors use to estimate the risk of the cancer spreading (metastasis). If you want to know more about your risk, ask your doctor to discuss it with you.

Treatment of kidney cancer

If you are diagnosed with localised kidney cancer, your doctor can recommend treating the cancer with partial nephrectomy, radical nephrectomy, active surveillance, radiofrequency ablation, or cryotherapy. Each procedure has its own advantages and disadvantages. The choice of treatment depends on your individual situation.

For smaller kidney cancers, partial nephrectomy (removing only part of the kidney) offers similar cancer control as radical nephrectomy (removing the entire kidney) while preserving more kidney function. Ask your doctor if your tumour’s size and location make partial nephrectomy a good option for you.

Both radical and partial nephrectomies can be performed through different methods: open surgery, laparoscopic (keyhole), or robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. The best approach depends on the tumour and the expertise of your medical team. Discuss your specific situation with your doctor to determine the most appropriate treatment.

If you have other health issues or are frail, ask your doctor about alternative treatments like active surveillance (regular monitoring) or tumour ablation. Ablation uses techniques like freezing (cryotherapy), heating (radiofrequency or microwave), or targeted radiation (stereotactic ablative radiotherapy) to destroy the tumour. While these treatments are less invasive, studies show they may have a higher risk of the cancer returning compared to partial nephrectomy.

If you are diagnosed with locally-advanced kidney cancer, your doctor can, in specific circumstances, recommend to treat the cancer with radical nephrectomy or embolisation. Each procedure has its own advantages and disadvantages. The choice of treatment depends on your individual situation.

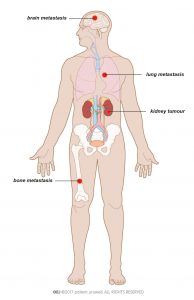

Kidney tumours can spread to other organs or distant lymph nodes. This is called metastatic disease. In metastatic disease, the kidney tumour is referred to as the primary tumour and the tumours in other organs are called metastases. Your doctor may recommend to treat metastatic disease with surgery, usually in combination with immunotherapy-based therapy. Antiangiogenic therapy, also known as targeted therapy, is usually used in combination with immunotherapy. For the treatment of metastases, radiotherapy may be recommended.

Generally, metastatic disease cannot be cured. The treatment of metastatic disease aims to reduce the size of the primary tumour and the metastases. This will give you the chance to live longer and have fewer symptoms.

Treatment of localised kidney cancer

If you are diagnosed with localised kidney cancer, your doctor can recommend treating the cancer with partial nephrectomy, radical nephrectomy, active surveillance, radiofrequency ablation, or cryotherapy. Each procedure has its own advantages and disadvantages. The choice of treatment depends on your individual situation.

This section describes the different treatment options, which you should discuss with your doctor.

This is general information which is not specified to your individual needs. Keep in mind that situations can vary in different countries.

Treatment options for localised kidney cancer

The best option for the treatment of a kidney tumour is surgical removal.

Localised kidney cancer can be removed through either partial nephrectomy or radical nephrectomy. Both procedures can be performed by open or laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic surgery can also be done with the aid of a surgical robot system.

During a partial nephrectomy only the tumour is removed, leaving the healthy kidney tissue untouched. This surgery is recommended whenever possible. If it is not possible to remove the whole tumour and leave part of the kidney intact, your doctor will recommend radical nephrectomy. This means that the kidney in which the tumour is located and the surrounding tissue are completely removed.

Sometimes, surgery may not be the best option for you. This may be because of your age or medical condition, for example.

If the tumour is smaller than 4 cm, your doctor may suggest a period of active surveillance. During active surveillance, your doctor schedules regular visits to monitor the tumour.

Active surveillance is a form of treatment for localised kidney cancer in which the doctor actively monitors the tumour. It is recommended if surgery is not the best option for you and you have a tumour in your kidney which is smaller than 4 cm.

Some of the reasons why your doctor may say you are unfit for surgery include your age or any medical conditions which make surgery dangerous for you. To determine if active surveillance is an option, your doctor may want to perform a renal tumour biopsy. The tumour tissue taken during biopsy is analysed to make sure it is not aggressive. If the tumour is aggressive and surveillance is not an option for you, you may be recommended further treatment.

If you are a good candidate for active surveillance, your doctor will set up a strict visiting schedule. On each visit, the urologist asks questions about any noticeable changes in your health, performs a physical examination, and discusses the results of your blood tests. Before each visit, you get a CT or an ultrasound scan of your abdomen to monitor the growth of the tumour.

In most cases, a follow-up visit is needed every 3 months in the first year after diagnosis. In the following 2 years the visits are scheduled every 6 months, and then once a year.

In general, small kidney tumours tend to grow slowly and the cancer rarely spreads to other organs. If tests during follow-up show that the tumour is growing fast, or if you develop symptoms which may indicate the disease is advancing, the urologist will immediately plan further treatment.

Options for further treatment include surgery to remove the tumour or the whole kidney, or ablation of the tumour.

Factors which influence the decision for the best treatment option include:

- Your age;

- Other medical problems you may have;

- The location and size of the tumour;

- The subtype and grade of the tumour.

If surgery is selected, partial nephrectomy should be favoured whenever possible. During this surgery, the tumour is removed but the surgeon leaves as much as possible of the healthy tissue of the kidney intact.

If the tumour continues to grow you may need further treatment. A good option in this case may be ablation therapy.

Ablation therapy can be either radiofrequency ablation (RFA), cryotherapy, microwave (MWA), or stereotactic radiotherapy. The aim of these procedures is to kill tumour cells by heating (RFA and MWA), freezing (cryotherapy), or radiation.

These are some topics you should discuss with your doctor when planning your treatment pathway:

- Your medical history;

- If there are any cases of kidney cancer in your family;

- What to consider if you only have one kidney;

- Whether your kidney function is normal or if it has already been affected by other conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure;

- Whether you have a tumour in one or both of your kidneys;

- The kind of treatment available at your hospital;

- Your personal preferences and values;

- Support during and after treatment;

- The expertise of your doctor. Ask your doctor about his or her experience with the recommended treatment option.

Follow-up of localised kidney cancer

After surgery you will meet with your doctor. In this visit, both the results of the surgery and the follow-up schedule will be discussed. Ask for a care plan so you can see how often you will need to see your doctor, and what kind of tests could be needed before each visit. This depends on the characteristics of the tumour.

Write down questions you may have before the visit. Examples of questions you can ask are:

- Is the cancer gone?

- Do I need additional treatment? If so, what options are relevant for me?

- What kind of tests do I need before the follow-up visits?

- How will the treatment and the kidney cancer affect my quality of life?

It is important that you continue to attend these visits. During these, the doctor monitors your kidney and can detect possible tumour recurrence on time. It is also important to tell your doctor if you notice any new symptoms. Do not hesitate to contact your health care team and tell them about new symptoms before the visit.

Treatment of locally-advanced kidney cancer

If you are diagnosed with locally-advanced kidney cancer, your doctor can recommend to treat the cancer with radical nephrectomy or embolization. Each procedure has its own advantages and disadvantages. The choice of treatment depends on your individual situation.

This section describes the different treatment options, which you should discuss with your doctor.

This is general information which is not specified to your individual needs. Keep in mind that situations can vary in different countries.

Treatment options for locally-advanced kidney cancer

The most common treatment to cure locally-advanced kidney cancer is surgical removal of the kidney which contains the tumour.

Locally-advanced kidney cancer can be treated with a procedure called radical nephrectomy. This means that the kidney where the tumour is located and the surrounding tissue are removed. Radical nephrectomy can be performed by open or laparoscopic surgery. If surgery is impossible or risky, the doctor may recommend embolisation.

These are some topics you should discuss with your doctor when planning your treatment pathway:

- Your medical history;

- If there are any cases of kidney cancer in your family;

- Your kidney function;

- What to consider if you only have one kidney;

- Whether you have one or more tumours in one or both of your kidneys;

- The kind of treatment available at your hospital;

- Your personal preferences and values;

- Support during and after treatment;

- The expertise of your doctor. Ask your doctor about his or her experience with the recommended treatment option.

Systemic treatment options for locally-advanced kidney cancer

Systemic treatment for locally-advanced kidney cancer can be given either before surgery (neoadjuvant) or after surgery (adjuvant). Neoadjuvant therapy, which is given before surgery, may help shrink the tumour and reduce blood clots, but because there isn’t enough strong evidence yet, it’s usually offered as part of a clinical trial. Adjuvant therapy, given after surgery, can include immunotherapy, which has been shown to improve survival in patients with locally-advanced kidney cancer and sometimes even in cases of localised kidney cancer. Talk to your doctor about these options and if they might be suitable for your situation.

Follow-up of locally-advanced kidney cancer

After surgery, you will meet with your doctor. In this visit, both the results of the surgery and the follow-up schedule will be discussed. Ask for a care plan so you can see how often you will need to see your doctor.

Write down questions you may have before the visit.

Examples of questions you can ask are:

- Is the cancer gone?

- Do I need additional treatment? If so, what options are relevant for me?

- What are the risks of the cancer coming back?

- How will the treatment and the kidney cancer affect my quality of life?

- What kind of tests do I need before the follow-up visits?

Treatment of metastatic kidney cancer

Kidney tumours can spread to other organs or distant lymph nodes. This is called metastatic disease. In metastatic disease, the kidney tumour is referred to as the primary tumour and the tumours in other organs are called metastases.

If kidney cancer metastasises, it generally spreads to the lungs, bones, distant lymph nodes, or the brain (Fig. 6). Metastases can be seen on a CT scan, either on initial diagnosis or during follow-up visits after treatment. They could also be detected because they cause symptoms.

Metastatic disease may be asymptomatic or can cause different symptoms, according to where the cancer has spread. The most frequent symptoms are a persistent cough in case of lung metastasis, or bone pain if the cancer has spread to the bones.

Your doctor may recommend to treat metastatic disease with surgery, usually in combination with immunotherapy-based therapy. Antiangiogenic therapy, is usually used in combination with immunotherapy.

Antiangiogenic therapy is a treatment option for metastatic kidney cancer.

These are a group of drugs which slow down tumour growth or possibly even shrink the tumour. They prevent the formation of new blood vessels which feed the cancer and allow it to grow. The formation of vessels is called neoangiogenesis, and the medical term for these drugs is antiangiogenic therapy.

Antiangiogenic therapy is often referred to as targeted therapy because it mainly affects the cancer cells. There are various types, each one targeting specific factors which influence tumour growth.

Most types of antiangiogenic therapy are pills which you can take at home. A few are administered through an IV, for which you will need to go to the hospital. For kidney cancer treatment, common antiangiogenic drugs are:

- Sunitinib

- Pazopanib

- Axitinib

- Cabozantinib

- Lenvatinib

- Tivozanib

- Bevacizumab (combined with immunotherapy)

For the treatment of metastases, radiotherapy may be recommended.

The treatment of metastatic disease aims to reduce the size of the primary tumour and the metastases. This will give you the chance to live longer and have fewer symptoms. This section describes the different treatment options, which you should discuss with your doctor.

This is general information which is not specified to your individual needs. Keep in mind that situations can vary in different countries.

Treatment options for metastatic kidney cancer

If you have metastatic disease, surgical removal of the kidney might be recommended to reduce the size of the tumour and relieve symptoms. This surgery is called cytoreductive nephrectomy. The procedure is only possible if you are fit enough to undergo surgery. If successful, you can live longer and with fewer side effects. Alternatively, renal artery embolisation could be used if you are unfit for surgery in order to shrink the primary tumour and relieve the symptoms.

If the metastases cause much pain or other symptoms, you may have further surgery to remove those metastatic tumours. Your doctor may recommend this if the tumours can be removed and you are fit for major surgery.

If the primary tumour is not very large or if your other kidney is not working well, your doctor may recommend cytoreductive partial nephrectomy. During this surgery, the doctor leaves as much as possible of the healthy kidney tissue intact.

In metastatic disease, surgery is generally combined with drug therapy. There are several types of drug treatment for kidney cancer:

- Immunotherapy-based combinations.

- Antiangiogenic therapy, commonly described as targeted therapy.

Your doctor may recommend drug treatment before surgery to shrink the tumour so it can be removed. If it responds well, treatment continues after surgery. It is also possible that your doctor recommends drug treatment only after surgery.

If surgery is not possible, you will start treatment with drug therapies right away. These drugs influence the mechanisms that tumours use to grow. Generally, immunotherapy-based combinations are used. antiangiogenic therapy is used. Drug therapy can relieve your symptoms and may shrink the primary tumour and the metastases.

If the metastases still cause symptoms after surgery or while you receive drug treatment, radiotherapy may help to relieve them further. These are some topics you should discuss with your doctor when planning your care pathway:

- Your medical history;

- Your kidney function;

- Whether you have one or more tumours in one or both of your kidneys;

- Where the cancer has spread to;

- The kind of treatment available at your hospital;

- Your personal preferences and values;

- Support during treatment;

- The expertise of your doctor. Ask your doctor about his or her experience with the recommended treatment option.

Sometimes recovery from kidney cancer is not possible. When treatment is no longer successful you may be offered palliative care to make you more comfortable. Palliative care is a concept of care with the goal to optimise your quality of life if you cannot recover from your illness.

Involving patients in their own treatment decisions is becoming increasingly important in cancer care, including for kidney cancer. Research shows that when patients are actively involved in reporting their symptoms and making decisions about their treatment, it can lead to better outcomes, including longer survival.

You should discuss your role in treatment decisions with your urologist. There are tools available to help support both you and your family in making these decisions together with your healthcare team.

Be actively involved in making decisions about your treatment! Working together with your urologist to make treatment choices can lead to better outcomes, so it’s highly encouraged.

Clinical trials

Another option that should be considered are clinical trials. This can be discussed with your doctor as well as when and where trails may be available in your area.

What is a clinical trial?

Clinical studies are typically designed to test how a treatment works among patients with specific characteristics, so not everyone will be eligible.

Why participate in a clinical trial?

Participating in a clinical trial has several advantages. You have the opportunity to be treated with drugs or devices that have been tested for safety and are not widely available. Your symptoms and general condition will also be monitored more often and more closely than during regular treatment.

It also important to know that you can stop your participation at any time. You will not need to explain your reasons.

General information about kidney cancer

Stages of kidney cancer

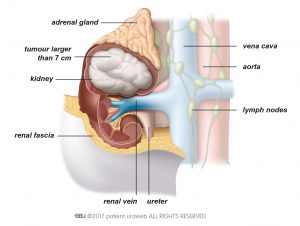

There are different stages of kidney cancer. If the tumour is limited to the kidney and has not spread, this is called localised kidney cancer. In locally advanced kidney cancer, the tumour has grown out of the kidney into surrounding tissue and invaded veins, the adrenal gland, or lymph nodes. Doctors speak of metastatic disease if the cancer has spread either to distant lymph nodes or other organs.

Risks factors for kidney cancer

The causes of kidney cancer are often difficult to determine. General risk factors are smoking and obesity.

Having a first-degree relative with kidney cancer or high blood pressure are also potential risk factors. Certain lifestyle changes, most importantly quitting smoking and keeping a healthy weight, may reduce the risk of developing kidney cancer.

Classification of kidney cancer

Kidney tumours are classified according to their stage, subtype, and the grade of aggressiveness of the tumour cells. These three elements are the basis for your possible treatment pathway.

Staging system

Tumour stage indicates how advanced the tumour is and whether or not there are metastases in the lymph nodes or other organs.

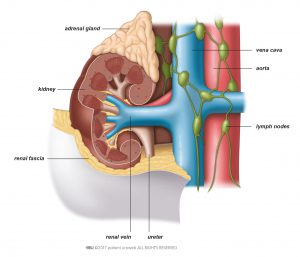

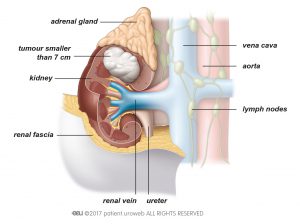

Kidney tumour stage is based on the Tumour Node Metastasis (TNM) classification. The urologist looks at the size and invasiveness of the tumour (T) and determines how advanced it is, based on 4 stages. Whether any lymph nodes are affected (N) or if the cancer has spread to any other parts of your body (M) is also checked. If kidney tumours metastasise they generally spread to the lungs, or to the bones or brain. Figures 1 to 5 illustrate the different stages.

Tumour subtype

Next to staging, the subtype of kidney tumours is important. The subtype is determined by a pathologist and the procedure is known as histopathological analysis. The specialist examines under a microscope the tumour tissue either taken during a biopsy or after it has been removed during surgery. Renal biopsy is not a standard procedure in the diagnosis of kidney cancer. In most cases, the subtype of your tumour will not be known until after you have surgery.

There are various subtypes of kidney tumours. Most kidney tumours are renal cell carcinomas. Of these, the most common subtype is clear cell renal cell carcinoma

If you are diagnosed with a rare kidney tumour your doctor will give you detailed information about different treatment possibilities. These may differ from therapy for the more common kidney cancer subtypes. Treatment options are discussed by a multidisciplinary team of doctors, to find the best approach for you.

Benign tumours

Some tumours in the kidney are non-cancerous. These are known as benign kidney tumours. The most common benign tumours of the kidney are oncocytomas and angiomyolipomas.

Oncocytomas are generally diagnosed after histopathological analysis, because scans cannot always identify them clearly. The most common treatment options for these tumours are partial nephrectomy and active surveillance. Read more about these treatment options in the section Localised Kidney Cancer.

An angiomyolipomas (AML) is a benign tumour and more likely to occur in women. It is generally diagnosed after ultrasound, CT or MRI scans, or if the tumour bleeds and causes symptoms. Although AML is a benign tumour, the risk of spontaneous bleeding in the kidney increases if it continues to grow. Surgery to remove the tumour is recommended if:

- You have a large AML (a tumour larger than 4 cm)

- You are a woman under the age of 45

- The tumour causes symptoms

- It is difficult for you to visit your doctor in case of emergency, because you live far away from a hospital or you have limited mobility.

Generally, an AML is removed with partial nephrectomy but in some cases it may be necessary to remove the whole kidney. Radical nephrectomy is recommended in case of severe bleeding of the tumour.

Renal cysts

Some masses in the kidney are not tumours but renal cysts. These are sacs filled with fluid located on the kidney and are easily recognised on a CT scan. Cysts can be malignant. If this is the case they need to be removed by surgery.

Grading system

The third component of the classification is an evaluation of how aggressive the tumour cells are. The Fuhrman nuclear grade is the most commonly used system to determine this. The pathologist classifies your tumour in 1 of 4 grades.

Individual prognosis

After diagnosis and classification, your doctor will discuss different treatment and follow-up options with you. The recommended treatment pathway is based on the TNM staging, the Fuhrman grade, and the subtype of the tumour. Your individual prognosis can also be estimated after classification. However, keep in mind that this is a prediction which does not take into account any unexpected developments.

In need of support?

The International Kidney Cancer Coalition (IKCC) is a global collaboration of patient organisations dedicated to kidney cancer patients.

Decision aid resources for people with renal cell carcinoma (kidney cancer)