Table of Contents [hide]

What is primary urethral cancer?

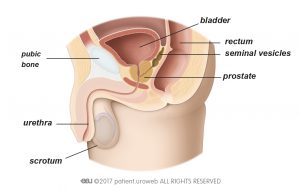

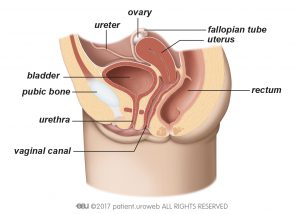

You have been diagnosed with primary urethral cancer. This means you have a cancerous growth (malignant tumour) in your urethra. The urethra carries urine out of the body from the bladder, also known as urinary bladder. In men, the urethra runs through the prostate and the penis (Fig. 1). In women, it leads to the genital area in front of the vagina (Fig. 2).

Primary urethral cancer is rare and is found more frequently in men and in patients older than age 75 years. It is not contagious.

A tumour that grows towards the centre of the urethra without growing into deeper layers or adjacent organs is superficial and represents an early stage of cancer. Urethral cancer becomes advanced as it grows into deeper layers of tissue; into the penis, the vagina, or adjacent organs; or into the surrounding muscles. This type of cancer has a higher chance of spreading to other parts of the body (metastatic disease) and is harder to treat. In some cases, it may be fatal.

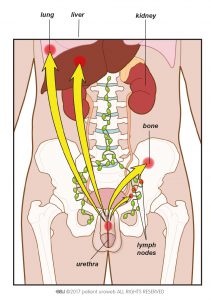

If urethral cancer spreads to other parts of the body such as the lymph nodes or other organs, it is called metastatic urethral cancer. At this stage, cure is unlikely, and treatment is limited to controlling the spread of the disease and reducing symptoms.

Symptoms of primary urethral cancer

Primary urethral cancer has no typical early symptoms. Most patients experience bloody discharge from the urethra (haematuria). If you have advanced cancer, you may be able to feel a hard mass in your genital tract. You have problems urinating if the tumour blocks the opening of your bladder or fills out the urethra completely. Other symptoms could be pain in your pelvis or during sexual activity. If you have these symptoms, it does not mean you have cancer, but you should be examined by your doctor.

Diagnosis of primary urethral cancer

If you have suspicious symptoms, your doctor will make a diagnosis to rule out cancer. Your doctor may take a detailed medical history and ask questions about your symptoms.

Clinical examination

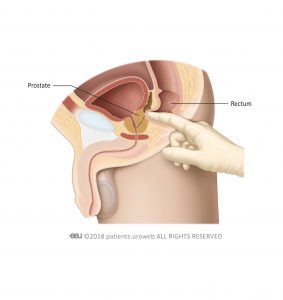

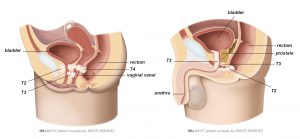

If you are male, your doctor will perform a digital rectal examination (Fig. 3) and a physical examination of the external genitalia in case a hard mass can be felt.

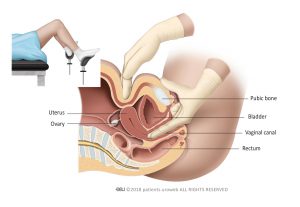

If you are female, your doctor will perform a careful examination of your external genital tract and a bimanual examination (Fig. 4) to exclude the presence of cancer in the colon, rectum, and reproductive organs. The bimanual examination can be performed under anaesthesia if it is painful for you. Your doctor will also feel the lower part of your abdomen, including the groin and the area above your pelvis, to detect enlarged lymph nodes.

Urine cytology

Your doctor may take a urine sample to look for cancer cells and to exclude other possibilities like urinary tract infection. Your doctor may refer to this test as urinary cytology, which means your urine is examined under a microscope to identify cancer cells.

Urethrocystoscopy and biopsy

The detection of urethral tumours depends on an internal examination of the urethra, called urethrocystoscopy. This test allows your doctor to look at the inside of your urethra and your bladder using a thin, lighted tube called a cystoscope.

After the urethra is anaesthetised, the cystoscope—a flexible or rigid tube connected to a camera that transmits pictures from inside your body—is inserted into the urethra and the bladder.

If a tumour can be seen or if a probe of fluid from the bladder contains cancer cells, tissue samples are needed for examination (biopsy). Small tissue samples can be taken immediately with the cystoscope.

Larger biopsies or removal of tumours also known as transurethral resection of the bladder tumour (TURBT) are usually done under general anaesthesia.

Imaging testing

If cancer is detected, your doctor will recommend further testing to determine the size and depth of the tumour and to detect or rule out possible spread to other organs or lymph nodes (metastatic disease).

Different imaging techniques are used to acquire this information, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan) and computed tomography (CT scan). Additional ultrasound may be useful to examine the lymph nodes in the abdomen.

MRI uses strong magnetic fields and radio waves to make images of your body. In urethral cancer, it is used to measure tumour size and depth in the pelvis. If you are allergic to contrast dye, MRI may be an alternative to CT to look for cancer spreading.

A CT scan gives your doctor information about the lymph nodes and abdominal organs. A contrast agent is injected into the body through a vein to improve the visibility of certain internal body parts and pathways during the CT scan. The scan, called CT urography, takes approximately 10 minutes and uses x-rays. It is the most accurate imaging technique for diagnosing cancer in the urinary tract.

CT urography is non-invasive, so no instruments are inserted into your body. For this examination, your kidneys must function adequately. The contrast agent can cause an allergic reaction, so please let your doctor know if you have had any allergic reactions in the past. The staff will also ask you about allergies. If you are taking any antidiabetic medications, your doctor might ask you to stop taking them for a few days.

Ultrasound is a non-invasive diagnostic tool that can visualise large masses in your pelvis. It cannot detect small tumours that have spread, and it cannot replace CT or MRI.

Treatment of primary urethral cancer

Localised urethral cancer

Localised primary urethral cancer is confined to the urethra. Treatment for men and women differs.

Your doctor will recommend a treatment that aims to remove all cancer and preserve your quality of life. To do this, the location of the tumour is important.

Locally-advanced primary urethral cancer

Advanced primary urethral cancer has grown into deeper layers of tissue, adjacent organs, or surrounding muscles. It has a higher chance of spreading to other parts of the body (metastatic disease) and is harder to treat.

Urothelial carcinoma of the prostate

Your doctor may recommend a urethra-sparing approach with transurethral resection of the prostate followed by chemotherapy if the cancer is non-invasive (Ta, T1).

In some cases, your doctor may recommend a cystoprostatectomy, which is a surgical procedure to remove your bladder, prostate and, in case your bladder and prostate contain cancer cells, an extended pelvic lymphadenectomy (removal of the lymph nodes in your pelvis).

Metastatic disease

If urethral cancer has spread to other parts of the body (Fig. 5), cure is unlikely. Treatment is limited to controlling the spread of the disease and reducing the symptoms.

Your doctor may recommend additional treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Often, a multidisciplinary team of urologists, radiation oncologists, and oncologists will discuss your case to find the best possible treatment option for you.

Bone metastases

Urethral cancer can spread to your bones. If this happens, skeletal complications can occur, such as weakening of the bones and fractures. These complications cause pain and can negatively affect your quality of life. Your doctor may suggest drug treatment to help strengthen your bones and control the pain.

Deciding on treatment

If treatment is intended to slow down the cancer and control the symptoms, deciding what treatment is best for you—or whether to have treatment at all—can be difficult. You will need a clear understanding of what chemotherapy can do for you at this stage and how it will affect your quality of life.

Prognosis

Prognostic factors for survival in primary urethral carcinoma are: age, race, tumour stage and grade, nodal stage, presence of distant metastasis, histological type, tumour size, tumour location, concomitant bladder cancer and type and modality of treatment

Clinical trials

If your urethral cancer has come back after treatment or has spread to other organs, you may be referred to centres where clinical trials are available.

What is a clinical trial?

These experimental studies are typically designed to test how a treatment works among patients with specific characteristics. Your doctor will provide all information you might need before participating in a trial. Your symptoms and general condition will be monitored more often and more closely than during regular treatment.

General information about primary urethral cancer

Risk factors for primary urethral cancer

Several biological factors and harmful substances can increase the risk of developing cancer. A higher risk does not necessarily mean that you will get cancer. Sometimes urethral cancer develops without any known cause.

Men may have a higher risk of primary urethral cancer if they have had radiation therapy, chronic inflammation, or a sexual transmitted disease. Using a catheter several times a day to urinate (intermittent catheter) also increases risk for men.

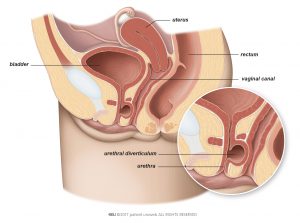

Women who have chronic infection or recurrent urinary tract infection may have an increased risk of primary urethral cancer. Development of a pouch (diverticulum) in the urethra also increases risk for women (Fig. 6).

Risk factors for urethral cancer:

- Age of 75 years or older—primary urethral cancer develops slowly and is more common in older people

- Urethral strictures or chronic irritation after intermittent catheter use or surgery in the urethra

- Radiation therapy (external or seed implantation) for other causes

- Chronic urethral inflammation or inflammation following a sexually transmitted disease

- Urethral diverticula and recurrent urinary tract infections

Staging and subtypes of primary urethral cancer

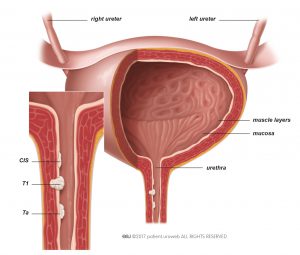

Tumours are classified by stage and subtype to describe the extent of cancer spread. The potential of the tumour to grow aggressively (tumour grade) will also be assessed. The kind of treatment you receive will depend on these elements. Tumour stage and subtype are based on whether or not the cancer is limited to the urethra (localised disease) (Fig. 7) and the degree to which the tumour has invaded the urethral wall (Fig. 8). This information, based on the TNM system, is important for determining the risk of recurrence (risk stratification) of the disease.

Stages Ta, T1, and Cis (Carcinoma in situ, also known as Tis) indicate that the tumour is localised in the urethra:

- Ta tumours are non-invasive finger-like protrusions on the urethral lining.

- T1 tumours have invaded the connective tissue under the urethral lining but have not grown into adjacent tissue.

CIS tumours are velvet-like tumours connected to the mucous tissue (mucosa) lining of the urethra. Stages T2, T3, and T4 indicate invasive urethral cancer.

Tumours have grown into the penis or the vaginal wall; the prostate; or the muscle tissue around the urethra, the bladder neck or adjacent organs. Lymph nodes or distant metastasis are detected by imaging techniques and graded for aggressiveness.

Follow-up

After surgery, your doctor will schedule you for a series of check-ups. During these visits, a urine sample will be checked for cancer cells, and your urethra will be examined with a cystoscope (urethrocystoscopy) and with imaging. Please be sure to attend these visits.

Regular check-ups are critical to ensuring that complications or disease recurrences are found early.

Support primary urethral cancer

Talk to family or friends and people who are close to you. It can help to discuss things with someone outside your inner circle. Your doctor may be able to refer you to a counsellor or specialist nurse.

Efforts are being made to promote patient advocacy for urethral cancer. Ask your oncologist if a urethral cancer patient representative is available near you. It may be helpful talk to a patient representative because urethral cancer is rare. Some of the treatments and side effects are comparable to those for bladder cancer.

Access to clinical trials

If your urethral cancer has come back after treatment or has spread to other organs, you may be referred to centres where clinical trials are available. These experimental studies are typically designed to test how a treatment works among patients with specific characteristics. Your doctor will provide all information you might need before participating in a trial. Your symptoms and general condition will be monitored more often and more closely than during regular treatment.

It is important to know that you can stop your participation in a clinical trial at any time. You will not need to explain your reasons.