Table of Contents

What is priapism?

What is the outlook?

Most people who experience priapism recover completely if treated quickly. Treating priapism quickly reduces the risk of permanent problems getting and keeping erections.

Causes of priapism

In most cases, the cause of priapism is unknown (idiopathic). However, patients who suffer from blood disorders, especially sickle cell disease, may develop priapism. Some blood, metabolic, or nervous system disorders and medications put patients at higher risk. In rare cases, priapism can affect children with sickle cell disease.

There are three types of priapism:

- Low-flow (ischaemic) priapism is the most common type. It happens when blood gets trapped in the penis. If not treated right away, it can lead to scarring and permanent erectile dysfunction.

- Intermittent (stuttering) priapism is a type of low-flow priapism characterised by repeating episodes of painful, prolonged erections.

- High-flow (non-ischemic) priapism is rarer and usually less painful. It typically happens after an injury to the penis or the area between the scrotum and the anus (perineum). The injury prevents blood in the penis from circulating normally.

Symptoms of priapism

- Rigid erection with or without sexual stimulation

- Erection lasts more than 4 hours

- Penile pain or sensitivity

Diagnosis of priapism

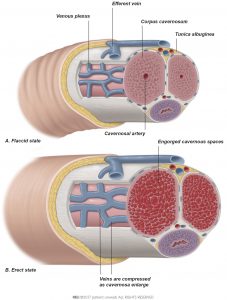

The penis is composed of two chambers (corpora cavernosa) and a mass of spongy tissue (corpus spongiosum). Erection results from relaxation of smooth muscle and increased blood flow into the corpora cavernosa. This causes engorgement and rigidity (see image below). In priapism, the corpus spongiosum and glans penis (the head) are not typically engorged.

Differentiating low-flow from high-flow priapism is critical because treatment for each is different. Your doctor might review your medical history and perform a physical examination to help determine the cause of priapism. Once the emergency is resolved, further blood tests might be prescribed to assess your blood health.

| Determining the type of priapism | |

| Medical history | Includes duration of erection, presence and degree of pain, previous history of priapism and its treatment, current erectile function, use of medication and drugs, other specific diseases (sickle cell disease), trauma to the penis or the area between the scrotum and anus (perineum) |

| Physical examination | Includes careful examination of the penis and the perineum |

| Blood tests | Includes blood aspiration and gas analysis from the corpora cavernosa of the penis to determine the type of priapism (a small needle is placed in the penis, some blood is drawn, and then it is sent to a laboratory for analysis) |

| Penile imaging | Includes penile colour Doppler ultrasound to show how blood is flowing in the penis and MRI to examine muscle health and look for fibrous tissue in the penis |

Treatment of priapism

The goal of any treatment for priapism is to make the erection go away and to prevent permanent erectile dysfunction.

- Low-flow priapism is an emergency and should be treated as soon as possible. The duration of the erection affects the severity of erectile dysfunction that can result.

- High-flow priapism might not require emergency treatment because blood flow to the penis is not reduced. However, only your doctor can distinguish between the two types or priapism.

If you suspect priapism, please contact your doctor immediately and do not attempt any home treatment.

Important: If you have any cardiovascular disease, be sure you tell your doctor before any treatment is performed.

Conservative, first- and second-line treatments

Conservative treatment options include exercise, ejaculation, and ice packs. However, they are rarely successful in resolving prolonged erections caused by low-flow priapism.

First-line treatment options are performed by a doctor. They are suggested for patients who have low-flow priapism lasting more than 4 hours. These treatment options are less likely to be successful when duration of priapism lasts more than 72 hours.

Second-line treatment typically refers to penile surgery. Surgery should be considered in cases of emergency, only when conservative and first-line treatment options have failed. Surgery is performed to minimise tissue damage from low blood flow to the penis and to reduce the chance of permanent erectile dysfunction.

| Treatment options | |

| Low-flow priapism | |

| Conservative | Do not attempt any home treatment. Please contact your doctor immediately. |

| First-line | The penis is numbed, and blood is drawn (aspiration) from the corpus cavernosum. Saline and medication are then injected (irrigation) into the penis to reduce pressure and swelling. |

| Second-line | Penile shunt surgery or penile prosthesis implantation. |

| High-flow priapism | |

| Conservative | Ice packs to the perineum or compression of the injury may bring down swelling. |

| First-line | Block the blood vessel that is causing the problem (artery embolisation). |

| Second-line | Surgical ligation to tie off the ruptured artery: this procedure is a final treatment option if blocking the artery has failed. |

| Intermittent (stuttering) priapism | |

| First-line | The treatment of each acute episode is similar to that of low-flow priapism. |

| Drug therapy | Hormonal therapies and/or antiandrogens or phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, depending on the patient’s medical profile. |