Table of Contents [hide]

What is muscle-invasive bladder cancer?

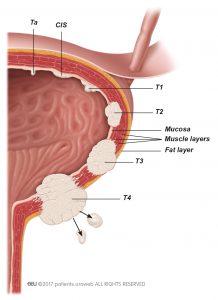

About a quarter of patients diagnosed with bladder cancer have a muscle-invasive form that has grown into the muscular part of the bladder wall (stages T2–T4). This type of cancer has a higher chance of spreading to other parts of the body (metastatic) and needs a different and more radical form of treatment. Muscle-invasive bladder cancer will be fatal if untreated.

Additional diagnostics

Computed tomography (CT scan) is particularly important for further work-up in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. With a whole-body CT scan, done in less than 10 minutes, the physician can tell if the cancer has already grown out of the bladder and into the surrounding tissue or adjacent organs and if there are signs of spreading to other organs (metastatic disease). By adding intravenous contrast agent, which is excreted into the urine by the kidneys, the urinary tract above the bladder can be visualised and tumour growth identified.

Prior to treatment, it is essential to evaluate whether the cancer is metastatic. If the CT scan indicates that the cancer has spread to your soft (visceral) organs, your bones or lymph nodes. This will possibly change the treatment decisions.

Additional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scans) or bone scans may be performed, although this is not routinely done. Bone and brain metastases are rare at the time that muscle-invasive bladder cancer is diagnosed. Therefore, your doctor would only consider a bone scan or additional brain imaging if you have specific symptoms that suggest bone or brain metastases. Unclear findings might also be probed with a needle biopsy to confirm metastatic disease.

A combination of positron emission tomography (PET scan; uses a radioactive tracer) and CT scan (PET/CT) is increasingly being used in European centres, although it is not generally available in all countries. PET/CT may improve the ability to detect distant metastases. It is not recommended for staging bladder tumours because urinary excretion of the radioactive tracer makes tumour staging very difficult.

Prognosis and risk stratification

The long-term prognosis for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer is determined by the extent of tumour growth (stage). As opposed to non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer aggressiveness (grade) which is determined by the pathologist is less important, since virtually all invasive tumours are high grade.

Treatment options for muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Removal of the urinary bladder (cystectomy)

The mainstay of treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer is surgical removal of the urinary bladder.

Bladder-sparing treatments

A bladder-sparing approach is currently used in a minority of cases worldwide but deserves consideration. Bladder preservation can be achieved at the cost of multiple therapies, including their side-effects. Transurethral resection of the bladder tumour (TURBT) and radiation is used to cure or control the tumour locally. Chemotherapy is used to treat the cancer cells that might already have spread within in the body (systemic disease). The goal is to preserve the bladder and its function as well as quality of life without compromising cancer treatment.

Studies in selected patient groups have shown good results for bladder-sparing approaches, about a third of patients still undergo bladder removal after failure of a bladder-sparing treatment.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumour

If you cannot undergo extended surgery, TURBT is possible if the tumour invades only the inner muscle layer of the bladder. With high recurrence and progression rates, this treatment alone cannot be considered a good option for controlling the disease long term.

Chemoradiation

Radiation therapy combined with sensitising chemotherapy is a reasonable alternative for patients who refuse or are not candidates for bladder removal. Evaluation of this approach will consider general fitness (life expectancy), kidney function, prior radiation, prior abdominal operations, and history of other cancers. A consultation with a radiation oncologist is advisable prior to deciding on this treatment.

Radiotherapy

Radiation therapy is an option for preserving the bladder in patients who are not candidates for surgery or who do not want surgery. Results from radiotherapy alone are worse than those from complete removal of the bladder, but if combined with chemotherapy (chemoradiation), acceptable results can be achieved. Side effects include mild to strong irritation of the bladder and digestive tract as well as incontinence, increased risk of infections, and fistulas (abnormal passages that develop between organs).

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone has only limited results and is not recommended as a sole treatment.