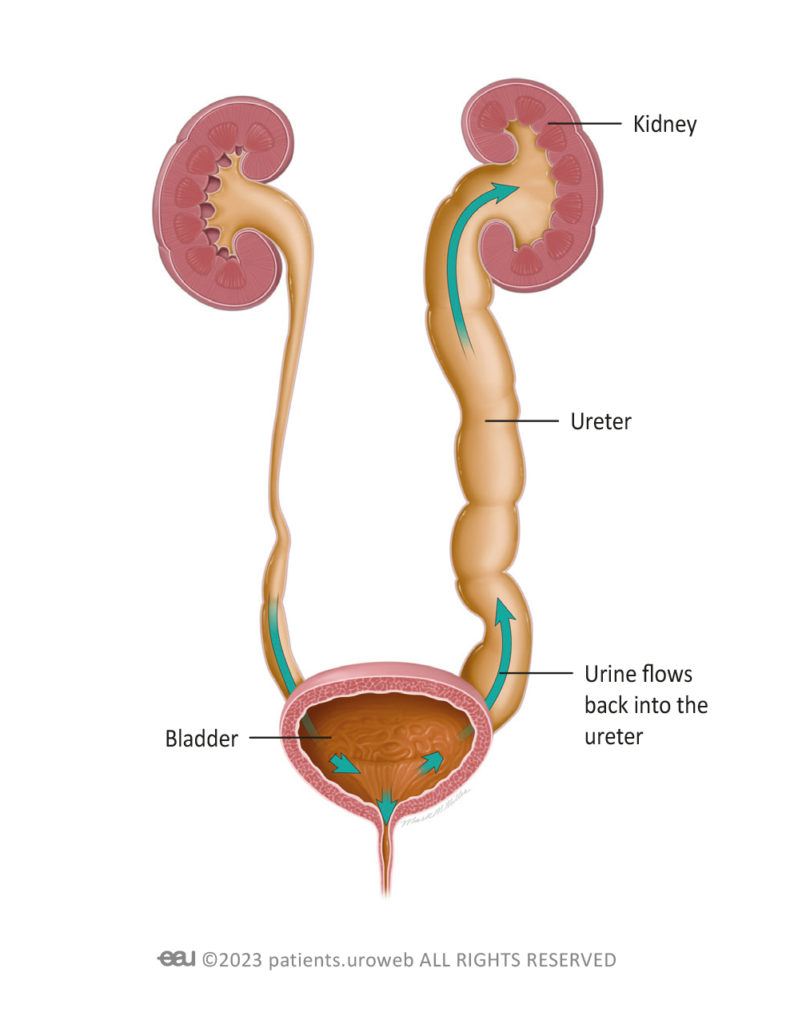

What is vesicoureteral reflux?

Vesicoureteral reflux (pronounced ‘vessy-co-yur-eet-er-ral ree-flux’), often shortened to VUR, is a condition where urine travels back up from the bladder, into one or both ureters and in severe cases, all the way back up to the kidneys. It happens when the valve that usually prevents urine from flowing backwards from the bladder is weakened or isn’t working properly.

Urine is a waste product and it is not supposed to flow back up through the urinary system. Urine passing back through the urinary tract can cause problems such as infection and damage to the kidneys.

VUR is graded from grade 1 to grade 5, with grade 1 being the mildest form, where urine flows from the bladder back only to the ureters, and grade 5 being the most severe, where the urine flows all the way up to the kidneys and causes significant stretching of the ureters and kidneys. More than 80% of VUR cases are graded as 2 or higher, which means that in most cases, the condition is moderate to severe.

Doctors use this grading system to help them propose the best treatment options.

VUR is present in about 2% of all newborn babies. Only a few children have noticeable symptoms. As children grow older and the bladder matures, diagnosis of this condition becomes less common.

VUR is sometimes found during a medical test such as a scan being carried out for other symptoms or another medical condition. It is more commonly seen in children who have congenital differences in their kidneys or other part of their urinary system, such as those with duplex kidney, ureterocele and ectopic ureters.

VUR is found to be the cause in 30-50% of children who have medical tests carried out for repeat UTIs.

If your child is diagnosed with VUR, their doctor will advise you if any treatment or further investigation is needed.

What are the symptoms of vesicoureteral reflux?

Usually, vesicoureteral reflux doesn’t cause any noticeable symptoms, but the most common is a UTI. In young children and babies, a UTI can be challenging to identify. The most common sign is a high fever. Alternatively, they may seem irritable or off their food.

In older children, signs of a UTI are easier to spot and include a burning sensation while peeing, having to pee a lot, cloudy or foul-smelling urine, and abdominal discomfort. An older child will also be able to better communicate with you about their symptoms.

How problematic is vesicoureteral reflux?

Children with VUR may experience repeat urinary infections, which require treatment and investigation as repeat infection can cause kidney damage. Your child’s doctor will be able to advise you about how severe their VUR is and how to manage the condition.

To grade your child’s VUR, doctors use a range of medical tests, to assess their renal (kidney or urinary) function in further detail. These tests include scans such as dimercaptosuccinic acid renal scanning (DMSA) which is a type of scan that involves a safe tracer dye being injected into your child’s arm. This dye works its way through the bloodstream and into the kidneys and it causes any scarred areas to glow up on a scan, so that doctors can check to see whether VUR has caused any damage to your child’s kidneys.

The results of tests such as this are used by doctors to diagnose and grade VUR and to work out how best to treat it.

Further testing may be needed if initial tests and scans are unable to provide all the information needed for the doctor to make a diagnosis. This includes tests to rule out other medical conditions..

Your child’s doctor will discuss any testing that is necessary to make a diagnosis, at each stage, with you so that you understand what tests are being proposed, why and what they entail, as well as if there are any risks involved.

What treatments are available for vesicoureteral reflux?

Non-surgical treatments

Your doctor may prescribe antibiotics to treat or to prevent infections caused by VUR. Antibiotics work to kill the bacteria causing the infection and help to reduce the discomfort associated with UTIs.

If a child is toilet trained, bladder re-training and treatment for any bladder issues can help to lower pressure in the bladder and effectively treat VUR.

Surgical Treatments

Surgery for VUR is usually based on correcting the underlying urinary differences. Procedures may involve repairing or making changes to the ureters to correct the urine flow and prevent VUR. The specific surgery offered will depend on factors such as the severity of the condition and the risk of further kidney damage.

Surgery for VUR is carried out under general anaesthesia. This is where your child is given medication to send them to sleep. Once they are asleep, they do not feel anything, nor will they remember the operation.

After the procedure, your child will be taken to the recovery area and closely monitored. Your healthcare team will provide instructions on wound care, pain management and any potential dietary or activity restrictions. It’s important to follow these instructions so that your child has a good recovery.

This procedure involves threading a synthetic (manufactured) implant up through the urethra (wee tube) using an endoscope (a long narrow surgical tool that has a camera at the end). This treatment is minimally-invasive (requires no cuts to be made to the skin) as it uses the existing opening of the urethra.

Endoscopic treatment with an implant can be an effective way of restoring the bladder’s valve mechanism without the need for open surgery (where a surgeon would cut open the skin).

It involves only a short hospital stay and a low risk of complications as there are no cuts to the skin, so there are no scars following surgery.

Your child’s doctor will assess their specific needs and provide you with the necessary information and guidance to make a decision about this treatment option if it is offered.

This surgery is typically performed when severe VUR is causing significant complications like frequent UTIs, or it is still causing problems even after endoscopic treatment.

With this type of surgery, the surgeon makes a small cut in the lower abdomen to reach the bladder, then carefully cuts away the ureter that isn’t working properly and repositions it, attaching it to another location in the bladder and in the process, restoring the valve mechanism so that the flow of urine is correctly controlled.

This surgery can be done in a minimally-invasive manner such as via laparoscopy or robotic surgery (where only small cuts to the skin are required rather than open surgery which would involve opening of the skin) in hospitals with these facilities.